This marks the first in a series of posts where the creators of Omeka projects talk about their content and process, and why they chose Omeka.

Eric Nolan Gonzaba (@EGonzaba) is a doctoral student in American history at George Mason University, and the creator of the site Wearing Gay History. His research interests revolve around the cultural politics of race and gender in late 20th century America, particularly 1970s African American and queer nightlife. Below, he answers our questions about that site, which has grown from a single collection to featuring many including clothing from all over the United States.

1. How did you first encounter the collection of t-shirts at the Chris Gonzalez Library and Archives (the original collection on the site)?

As Outreach Coordinator for the GLBT Student Support Services Office at Indiana University during my undergraduate days, I spearheaded a project to build a small exhibit on the history of LGBT Hoosiers. There was just a few problems with this task; was I the only queer person to ever live in Indiana? If so, this exhibit isn’t going to be all that long. Ok, obviously gay people lived in Indiana before me, but where was I going to find the materials that made up their history?

I first visited the Chris Gonzalez Library and Archives in Indianapolis in 2011 to hunt for this lost account. Under the management of archivist Michael Bohr, the location is an impressive library and depository of LGBT books, films, papers, and ephemera documenting primarily the history of queer people of the greater Indianapolis area. While browsing the archival holdings, I came across a number of cardboard boxes on the floor filled with t-shirts and ball caps. With a lack of care that would scare most preservationists, I dove into those boxes finding all sorts of clothing tied to Pride parades, gay bars, lesbian bookstores, and political rallies.

What drew me to these items was their vividly intimate connection to queer Hoosier experiences. So much discussion of LGBT culture is obsessed with “the closet” — the hiding of sexual orientation from the public and what that fear of coming out has done to notions of agency. Certainly, the pressures of mainstream society to hide queer identities should not be overlooked, but these diverse LGBT-themed t-shirts serve as a perfect metaphor of a closet not ever fully closed. In fact, sometimes it was fully ransacked.

2. Why did you decide to use Omeka for this project?

As part of the doctoral program at George Mason University’s Department of History and Art History, PhD students are required to become digitally competent. Since the word “novice” doesn’t fully describe my lack of IT skills in my first semester in the program, I began Dr. Stephen Robertson’s History and New Media course with excitement. Each week, the class was introduced to different tools that define the field of digital history. During our Omeka week, I was drawn to the platform’s ease of use and its ability to combine different aspects of archiving, exhibit making, and mapping. It didn’t hurt that Omeka was created at Mason, but more than that, I was impressed about how easy it was to actually use software that I never before encountered.

3. Has using Omeka changed the way you thought about the project, especially early on?

Absolutely! While it was fun to track down a whole bunch of related historical items, in this case t-shirts related to LGBT experiences (some with enormously clever slogans like “Lesbiana Jones and the U-Haul of Doom”), it’s another thing entirely to actually get those items processed into a coherent digital archive. Omeka’s use of the Dublin Core Metadata standard helped me standardize information related to collection.

Additionally, the tag feature allowed me to think about the t-shirts in the collection not as individual items but as part of different select themes. This became especially helpful later on when I introduced other collections to the site. Wearing Gay History, which began with one collection and 300 t-shirts, now includes 10 collections with more than 2,500 items! The tag feature permitted me to link t-shirts together across the boundaries of individual collections, placing t-shirts relating to African Americans in San Francisco, for example, with t-shirts found in Harlem’s Schomburg Center of Research in Black Culture.

4. Since you first launched Wearing Gay History, the collections have grown tremendously and it has received positive publicity. How has this influenced your scholarship and your graduate work?

The response to Wearing Gay History has been tremendous, with the site featured in places like Slate, OutHistory, Quist, and Lawyers, Guns, and Money. I couldn’t imagine that would ever happen, especially as the site started as a simple student project from a graduate student who had just learned how to take a screenshot on his Macbook only weeks earlier. It’s a testament to what can come from a love of history and a newfound obsession with digital archiving.

The project has opened more doors for me than perhaps anything I’ve done in my academic career. I’ve gotten to visit numerous LGBT archives across the United States to witness the extraordinary work being done to preserve our queer past. Places like the Minneapolis’s Tretter Collection and Philadelphia’s Wilcox Archives diligently document the incredible diversity of LGBT experiences. It’s been a huge honor to partner with them to aid in their archiving work.

Along the way, conversations with queer historians I’ve admired for years like Claire Potter and John D’Emilo have brought me into a whole new community of scholars looking for new ways to conduct the study of sexuality. Even if my dissertation won’t solely be focused on LGBT textiles, the stories held within these pieces of fabric certainly have made a profound impact on how I think of past LGBT communities.

5. What is one of your favorite items to highlight when you talk about the project?

That’s sort of like asking me to name my favorite child, so easy — it’s Honey Boo Boo.

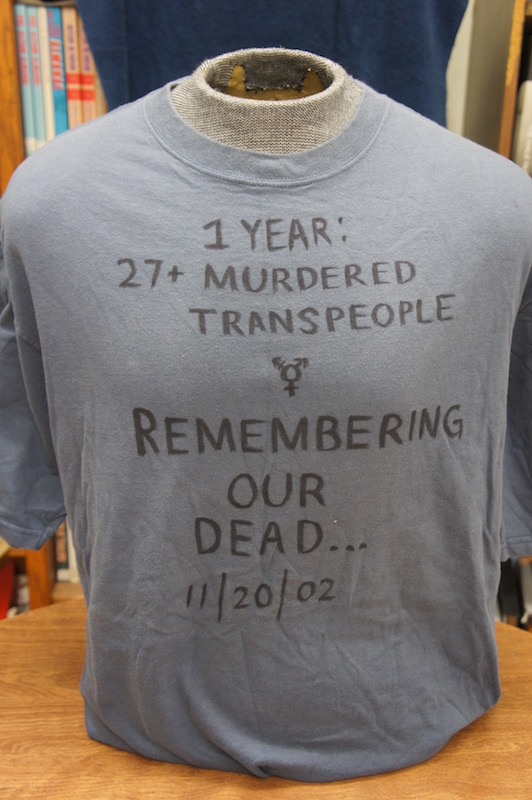

Okay, but in all seriousness, so many t-shirts in the collection mean a great deal to me because they relate to such important events and themes in our often overlooked histories. But in an effort not to evade the question, one textile I always come back to is entitled Remembering Our Dead. While the t-shirt is only fourteen years old, it’s completely handwritten by an activist who protested the violent abuse and murder of transgender bodies in the early part of the new millennium. The creator of the t-shirt, whose name is (so far) lost to history, took the time to spell out and list the more than 27 trans people murdered between 2001-2002.

Remembering Our Dead stands out for so many reasons. First, it’s one of just 14 t-shirts found on the digital archive that deal solely with transgender communities (bisexuals, unfortunately, fare even worse in the Wearing Gay History collections, a matter I hope to address with the increased visibility of the site in the coming months). More importantly, however, it’s distressing how little has changed since the t-shirt’s construction. Today, the vast majority of anti-LGBT violence is directed toward trans people, specifically trans women of color. The t-shirt teaches how important clothing can be in promoting social justice. At the same time, it serves as a stark reminder that the past isn’t really over.